MORE THAN HUMAN:THE ANIMAL IN THE AGE OF THE ANTHROPOCENE 12 Feb — 13 Mar 2020ANU School of Art & Design Gallery,Australian National UniversityActon ACTCurators: Dr Natasha Fijn and Julian Laffan

The Anthropocene is a geologic time scale where humans are leaving an indelible mark upon the earth. In this ‘age of the human’, is there a place for non-human life in this rapidly changing world? This exhibition brings together artists working across a range of media who are concerned with featuring the agency and subjectivity of the animal perspective on the Anthropocene.

Surya Bajracharya • GW Bot • Julian Davies • Natasha Fijn • Aidan Hartshorn • Ellis Hutch • Julian Laffan • Robert Nugent • Rebecca Mayo • Amanda Stuart • Antonia Throsby • Warlukurlangu Artists Corporation

RAT-RUNS AND WORM HOLESRebecca Mayocatalogue essay

For the last three years I have commuted between my home in Melbourne and work in Canberra. The to-and-fro between cities has led, perhaps counterintuitively, to a narrowing of focus. Rather than taking advantage of cultural offerings, or catching up with friends, I instead inhabited repetitive rat-runs ferrying children between weekend sport and home, walking my local creek or, while in Canberra, cycling between home and work. Our garden is more overgrown than before, the abundant ruby grapefruit (Citrus × paradisi) overhangs the fence and rests along the rainwater tank, the native raspberry (Rubus parvifolius) competes with blackberry (Rubus fruticosus), suckering unexpectedly and overrunning the garden.

The weekly absences changed my relationship with the garden from a productive site to an overgrown rear window. On the weekends, if I observed something novel, I came to expect my family not to have noticed or to tell me, ‘Oh it’s been like that for ages’. Time and space folded and wrapped, compressed and expanded, shaping new ways to understand our garden. As a commuter I became more aware of—and increasingly uncomfortable at my complicity in—mass human movement. Meanwhile, the garden had become a thoroughfare, rarely a place we stopped to spend time in.

I spent time each weekend tending the worms (Eisenia fetida & Lumbricus rubellus) in our compost. I love their wriggly bodies and how their quiet work making soil diverts food scraps from landfill. Over time the local rats (Rattus rattus), attracted to our area by our overgrown yard and neighbouring cafés and restaurants, seemed increasingly active and cheeky, busying themselves in daylight as well as after dark. Situating my practice with the worms and rats brought me back down to earth.

Charles Darwin’s 1881 book The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms was the culmination of 40 years of observational research on a European earthworm (Lumbricus terrestris)[1]. His research, conducted at home, with and amongst family, is slow and patient. An otherworldly methodology to the contemporary reader, it connects with practices like permaculture and art, which require reflection and observation as much as action. Maria Puig de la Bellacasa has explained the ethics of such practices as ‘situated ethics’, where one size does not fit all, but rather decisions are made depending on observed or measured conditions.[2] Such work improves with repetition, allowing knowledge and experience to accumulate. Puig de la Bellacasa calls this ‘care-time’.[3] At Work with Worms is a compost/composite of Darwin’s laser-etched text, my human tending, and the worms’ business of eating. Working with the thousands of worms contained in the farm, my making slowed to their rhythm. Etched in Canberra and left for a week with the worms, the book pages took up the worms’ appetite which in turn paced with the climate inside their home.

Rather than attempting to work with rats, I instead positioned a motion sensor camera near ground level. The camera has two sensors which trigger the camera to roll. Despite some native animals visiting the garden, none were clearly documented on film (ringtail possums also love our garden but tend not to venture to ground level).

Sitting down to write this essay, I googled ‘rats’ to make sure it is Rattus rattus who lives with us. The top search results were pest control businesses, unambiguously listing the many diseases rats carry and can pass on to humans. Reading details of the diseases I felt a wash of paranoia: what if gallery visitors think I am dirty, or irresponsible for allowing vermin to co-exist in our garden? Further reading revealed few diseases are present in Australia. For example, Tularaemia, a rare bacterial disease endemic to America, has only three recorded cases in Australia, two from scratches and bites from ring-tailed possums (2017) and one from contaminated water (2003)[4]. No mention of rats. What is it about rats that makes us all so twitchy? They can damage electric cables and buildings, so we should keep them outside. But are they actually carrying more disease than other mammals whom we might love to see in our gardens? Living in a built-up area, surrounded by cafes and restaurants, necessarily means we live closely with other feral species. In the past, we have used chemical pesticide to bait the rats. However, I can no longer be party to this slow and cruel death. Adding to my resolve is the possibility of the poison entering the food chain and killing a bird of prey.

The first time I set up the camera, I wondered if I would capture rats on film. I was surprised to see how active they were, mostly using garden structures as runways. Wherever I positioned the camera, the rats seemed to be. My family also knew the cameras were there, but in the bustle of life we forgot about them. The footage documents how we all use the garden, as a thoroughfare, or a place to quickly eat our lunch. The birds and rats in the garden seemed much more attuned to us than vice versa. On film they scurried away at the sound of close voices or human activity. We, by contrast, marched through the garden, echoing my longer weekly commutes. The camera enables a viewpoint which is low, more at animal height. Although I controlled the camera’s placement, it captured a point of view which showed species in relation with each other. Capturing the rats whizzing around our garden, as humans do at a larger scale around the globe, poses questions: When does an animal population shift, in reality or imagination, from benevolent equilibrium to vermin? On what grounds do we make such judgements?

[1] This species is invasive to Australia, and in fact, has many different behaviours to the compost worms in our worm farm. All three species improve soil quality through their consumption and digestion of matter.

[2] DE LA BELLACASA, MARÍA PUIG. “Alterbiopolitics.” In Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds, 150. Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press, 2017. Accessed February 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt1mmfspt.7.

[3] DE LA BELLACASA, MARÍA PUIG. “Soil Times: The Pace of Ecological Care.” In Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds, 201. Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press, 2017. Accessed February 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt1mmfspt.8.

[4] https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/Infectious/factsheets/Pages/tularemia.aspx (accessed February 7, 2020)

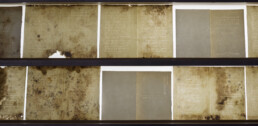

At Work with Worms

2020

laser etched and worm eaten paper, light boxes

1800 x 195 x 1800mm

photography: Brenton McGeachie

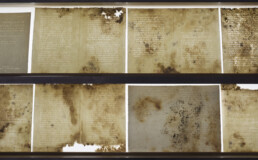

At Work with Worms

2020

laser etched and worm eaten paper, light boxes

detail (1800 x 195 x 1800mm)

photography: Brenton McGeachie

Comings and Goings

2020

1/5, dual channel video,

duration: 00:01:47 & 00:11:14